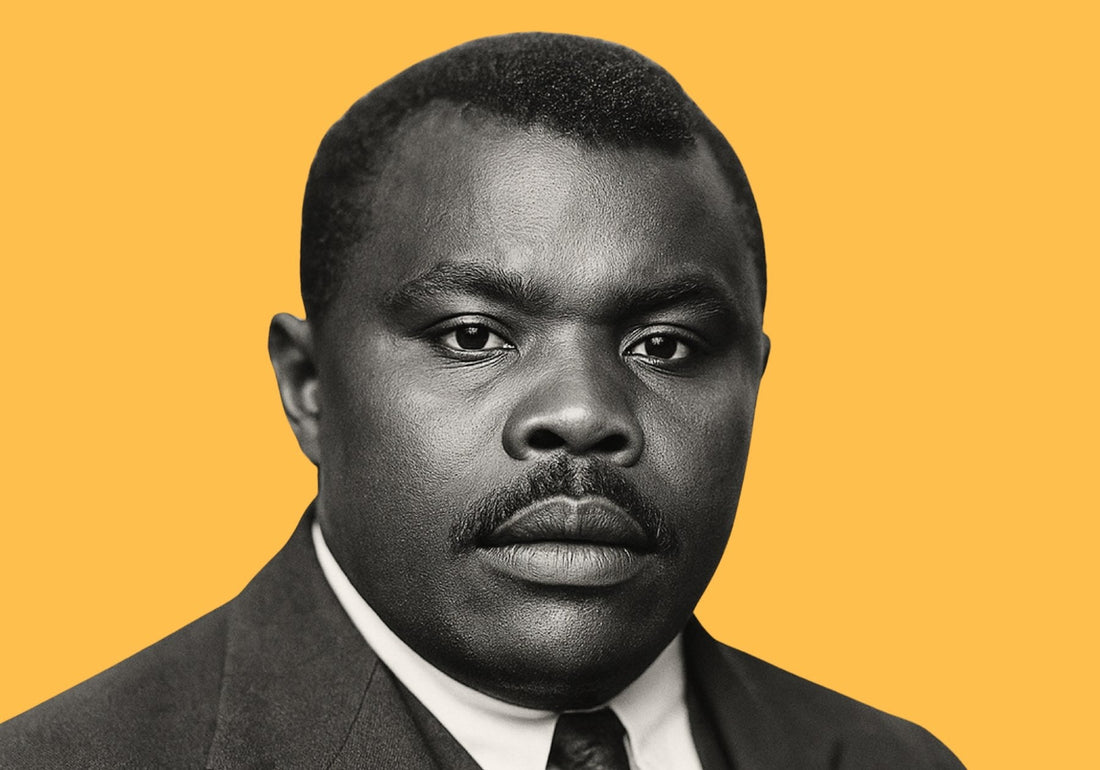

Marcus Garvey: The visionary of diaspora culture pride who changed history forever

Share

Introduction

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr., born on August 17, 1887, in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica, created the largest Black mass movement in modern history and fundamentally transformed how people of African descent saw themselves and their place in the world. His Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) claimed between 4 and 6 million members at its peak in the early 1920s, while his philosophy of Black pride, economic independence, and Pan-Africanism influenced everyone from Malcolm X to Bob Marley to modern hip-hop artists who celebrate his enduring legacy.

The son of a stonemason and a domestic worker, Garvey was the youngest of eleven children, though only he and his sister Indiana survived to adulthood. His father, whom Garvey described as "severe, firm, determined, bold, and strong," owned a small library where young Marcus discovered his love of reading. This early exposure to books would prove transformative, as would his first encounter with racism when a close white female friend's parents forbade her from associating with him, using racial slurs that made clear their hatred was based solely on his skin color. These formative experiences in colonial Jamaica shaped the man who would later declare that "a Black skin is not a badge of shame, but rather a glorious symbol of national greatness."

From Jamaica to the world stage

Garvey's journey from a small Jamaican town to international prominence began with his apprenticeship at age 14 in his godfather's printing business. By 1907, he had become Jamaica's first Black master printer and foreman, but his involvement in an unsuccessful printers' strike in 1908 led to his blacklisting from private employment. This early taste of labor organizing and racial discrimination pushed him toward journalism and activism, founding his first newspaper, "Garvey's Watchman," in 1909.

His travels through Central America between 1910 and 1912 exposed him to the horrific conditions faced by Black workers on banana plantations and at the Panama Canal. In Costa Rica and Panama, he edited newspapers advocating for workers' rights, experiences that deepened his understanding of the global nature of Black oppression. But it was his time in London from 1912 to 1914 that truly transformed his worldview. Studying at Birkbeck College and working for Dusé Mohamed Ali's pioneering Pan-African journal, the "African Times and Orient Review," Garvey immersed himself in the intellectual currents of Pan-Africanism. Reading Booker T. Washington's "Up from Slavery" in the British Museum library provided the final catalyst for his vision of Black self-help and economic independence.

On July 20, 1914, shortly after returning to Jamaica, Garvey co-founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League with Amy Ashwood. The organization's initial reception in Jamaica was lukewarm, prompting Garvey to seek a larger stage. On March 24, 1916, he arrived in New York City "penniless," lodging with a Jamaican family in Harlem while working as a printer by day and speaking on street corners by night.

Building an empire in Harlem

Garvey's breakthrough came on June 12, 1917, when he delivered a pivotal speech at Bethel AME Church in Harlem. The response was electric, and by May 1917, he had established the New York branch of UNIA with headquarters at Liberty Hall, located at 114 West 138th Street. This 6,000-capacity venue, a former Baptist church, became the nerve center of a global movement that would soon boast 700 branches in 38 states and over 1,900 divisions in more than 40 countries.

The UNIA was far more than a political organization. It created an entire parallel society with its own businesses, newspapers, religious institutions, and even a paramilitary wing. The African Legion, dressed in military uniforms, the Black Cross Nurses in their crisp white uniforms, and the Universal Motor Corps presented a vision of Black power and dignity that had never been seen before on such a scale. Weekly meetings at Liberty Hall drew thousands, while Garvey's newspaper, the "Negro World," launched in August 1918, reached a circulation of 200,000 and was distributed in over 40 countries—so influential that British and French colonial authorities banned it.

The pinnacle of Garvey's influence came during the First International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World in August 1920. For an entire month, Madison Square Garden and Liberty Hall hosted delegates from 25 countries. The convention's opening parade on August 3 stretched from 130th to 140th Street, featuring 5,000 uniformed UNIA members marching through Harlem. The spectacle was unprecedented—Black people displaying power, organization, and pride on a massive scale. The convention adopted the red, black, and green flag as the official colors of the African race, established "Ethiopia, Thou Land of Our Fathers" as an anthem, and elected Garvey as "Provisional President of Africa."

The Black Star Line: Dreams of economic independence

Perhaps no aspect of Garvey's movement captured the imagination—and ultimately proved as controversial—as the Black Star Line Steamship Corporation. Incorporated on June 27, 1919, with an initial capitalization of $500,000 (later increased to $10 million), the shipping company represented Garvey's vision of Black economic self-sufficiency on a global scale. The company sold shares at $5 each to ordinary Black Americans—cooks, porters, washerwomen—who invested their life savings in the dream of Black-owned ships connecting Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas.

The Black Star Line purchased three ships: the S.S. Yarmouth (which Garvey intended to rename the Frederick Douglass), the S.S. Shadyside, and the S.S. Kanawha. The vision was revolutionary—a Black-owned shipping line that would facilitate trade among the African diaspora and eventually transport settlers to Africa. Stock certificates featured images of Africa as the "Land of Opportunity," and thousands of shareholders proudly displayed them in their homes, creating early examples of what would today be recognized as Marcus Garvey posters and collectibles.

However, the enterprise faced insurmountable challenges. The ships were purchased at inflated prices and required constant repairs. The Yarmouth, bought for $165,000, was worth only about $25,000. Mismanagement, lack of shipping experience, and what many historians now recognize as deliberate sabotage by government agents led to massive losses. FBI documents later revealed that J. Edgar Hoover had specifically targeted Garvey for investigation as early as October 1919, with the Bureau hiring its first Black agents, including James Wormley Jones (Agent 800), to infiltrate the UNIA.

Philosophy that shaped movements

Garvey's philosophy centered on several revolutionary concepts that challenged the prevailing approaches to racial progress. His "Africa for Africans" ideology didn't necessarily mean all Black people should return to Africa, but rather that Africa should be controlled by Africans and serve as a power base for the global Black population. He promoted strict racial pride and self-reliance, arguing that "no race in the world is so just as to give others, for the asking, a square deal in things economic, political and social."

This philosophy brought him into direct conflict with other Black leaders, particularly W.E.B. Du Bois. While Du Bois advocated for the "Talented Tenth" and integration, Garvey appealed to the masses with a message of separation and self-determination. The conflict between the two men became viciously personal, with Du Bois calling Garvey "the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and the world" and describing him as "a little fat black man, ugly but with intelligent eyes and big head." Garvey responded by calling Du Bois "a hater of dark people" and criticizing the NAACP's light-skinned leadership.

Despite these conflicts, or perhaps because of them, Garvey's influence on the Harlem Renaissance was profound. His mass movement created the audience that Renaissance artists needed, while his emphasis on African heritage and Black pride provided themes that writers and artists would explore throughout the 1920s. The Negro World published poetry and commentary that competed with Du Bois's The Crisis for intellectual leadership of Black America. Under Amy Jacques Garvey's editorship, the paper even featured a full page called "Our Women and What They Think," providing a platform for Black women's voices during the Renaissance. This intersection of cultural movements continues to inspire modern interpretations, as explored in "The Harlem Renaissance Re-Imagined" and the fusion of "Art Deco, Bauhaus, and Harlem Renaissance" design principles.

Legal persecution and exile

The success of Garvey's movement made him a target of the U.S. government. In January 1922, he was arrested and charged with mail fraud for allegedly using the mail to sell stock in a ship the Black Star Line didn't yet own. The trial, which began in May 1923, was riddled with irregularities. Garvey dismissed his lawyer and represented himself, a decision that proved disastrous. The prosecution's key witness, 19-year-old Schuyler Cargill, admitted during cross-examination that prosecutor Maxwell Mattuck had instructed him to lie about dates—clear perjury that should have ended the case.

On June 18, 1923, Garvey was convicted and sentenced to five years in federal prison, though his three co-defendants were acquitted. He served nearly three years in Atlanta Federal Penitentiary before President Calvin Coolidge commuted his sentence in November 1927. The condition of commutation was immediate deportation. On December 3, 1927, approximately 1,000 supporters bid farewell as Garvey departed New Orleans on the S.S. Saramacca.

Back in Jamaica, Garvey attempted to rebuild his movement, founding the People's Political Party in 1929—Jamaica's first modern political party. He won a seat on the Kingston city council and started a new newspaper, "The Blackman." However, his influence had waned. In 1935, he moved to London, leaving his wife Amy Jacques and their two sons in Jamaica. He continued speaking at Hyde Park's Speakers' Corner and attempted to coordinate UNIA activities, but financial difficulties and declining health took their toll. On June 10, 1940, Garvey died in London at age 52 after suffering two strokes, having read his own premature obituaries in his final days.

A park, a legacy, and continuing influence

In 1973, New York City renamed Mount Morris Park in Harlem as Marcus Garvey Park, recognizing his profound impact on the community. The 20-acre park, bounded by 120th to 124th Streets between Madison and Fifth Avenues, had served Harlem since 1840. The renaming came after years of community activism, with groups like "The Community Thing" and the African Nationalist Activist Movement pushing for recognition of Garvey's legacy. Today, the park features the historic Mount Morris Fire Watchtower—the only surviving cast-iron fire watchtower in America—and the Richard Rodgers Amphitheater, which hosts the annual Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and other cultural events.

Garvey's influence on subsequent civil rights leaders cannot be overstated. Malcolm X's parents, Earl and Louise Little, were devoted Garveyites who met through UNIA activities. Malcolm credited his early exposure to Black nationalism to Garvey's teachings, acknowledging that Garvey "gave a sense of dignity to the Black people" and "organized one of the largest mass movements that ever existed in this country." Even Martin Luther King Jr., despite philosophical differences with Black nationalism, recognized Garvey as "the first man on a mass scale and level to give millions of Negroes a sense of dignity and destiny."

The Rastafari movement venerates Garvey as a visionary, interpreting his statement to "look to Africa for the crowning of a Black king" as prophecy of Haile Selassie's coronation. Bob Marley immortalized Garvey's words "emancipate yourself from mental slavery" in his song "Redemption Song," introducing Garvey's philosophy to new generations. Ghana honored Garvey by naming its national shipping line the "Black Star Line" and incorporating a black star into its flag.

Modern relevance in art, education, and culture

Today, Garvey's image and words permeate popular culture in ways he might never have imagined. His portrait and quotes have become powerful symbols of Black pride and resistance, appearing everywhere from protest signs to album covers, from community murals to Marcus Garvey clothing worn as statements of cultural identity. Contemporary artists create Marcus Garvey art that ranges from faithful historical portraits to modern interpretations incorporating hip-hop aesthetics and Afrofuturist themes. These items serve not just as fashion statements but as declarations of cultural pride and political consciousness.

Educational institutions bearing Garvey's name, such as the Marcus Garvey Academy in Detroit and the Frederick Douglass Marcus Garvey Academy, implement African-centered curricula emphasizing cultural awareness and community empowerment. These schools embody Garvey's belief that "a people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots"—a quote that remains ubiquitous in discussions about education and cultural preservation.

Garvey's economic philosophy finds new expression in movements promoting Black-owned businesses and economic cooperation. His famous exhortation, "Up, you mighty race, accomplish what you will," appears on motivational Marcus Garvey posters and social media posts, inspiring new generations of entrepreneurs and activists. His emphasis on self-confidence—"If you have no confidence in self, you are twice defeated in the race of life"—resonates in contemporary self-help and empowerment contexts.

On January 19, 2025, President Joe Biden granted Garvey a posthumous presidential pardon, acknowledging the political motivation behind his 1923 conviction. This vindication, coming more than a century after his persecution began, reflects growing recognition of how government forces targeted Black leaders who challenged systemic racism. Jamaica had already honored Garvey as its first National Hero in 1964, repatriating his remains from London to a memorial in Kingston's National Heroes Park.

The visionary's enduring message

Marcus Garvey's legacy transcends any single movement or era. His vision of Black pride, economic independence, and global Pan-African unity laid foundations that subsequent movements would build upon. From the Nation of Islam to the Black Power movement, from Rastafarianism to contemporary Pan-Africanism, his influence reverberates through every significant Black liberation movement of the past century.

Modern expressions of Garvey's legacy—whether through Marcus Garvey shirts worn at protests, academic conferences examining his philosophy, or digital art shared on social media—demonstrate the enduring relevance of his core message. His insistence that Black people must "canonize our own saints, create our own martyrs" finds expression in contemporary movements to recognize Black historical figures and challenge Eurocentric narratives.

The UNIA's motto, "One God! One Aim! One Destiny!" continues to inspire unity among people of African descent globally. Garvey's revolutionary act of making Black people see themselves as beautiful, powerful, and capable of determining their own destiny transformed consciousness in ways that reverberate today. Every expression of Black pride, every call for economic justice, every assertion of African cultural value carries echoes of the man from St. Ann's Bay who dared to envision a world where Black people stood equal to any.

As we navigate contemporary struggles for racial justice and economic equity, Garvey's words ring with prophetic clarity: "Liberate the minds of men and ultimately you will liberate the bodies of men." His legacy reminds us that true liberation begins with how we see ourselves, extends through economic and political organization, and ultimately requires the courage to imagine and build new realities. Whether expressed through art, education, business, or activism, the spirit of Marcus Garvey continues to inspire those who dare to accomplish what they will.

References

-

"The 1920 Convention of the Universal Negro Improvement Association." PBS American Experience. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/garvey-unia-convention/

-

"Black Nationalism." The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/black-nationalism

-

"Howard University School of Law Professors and Students Secure Posthumous Pardon for Civil Rights Leader Marcus Garvey." The Dig at Howard University, 2025. https://thedig.howard.edu/all-stories/howard-university-school-law-professors-and-students-secure-posthumous-pardon-civil-rights-leader

-

"Marcus Garvey (August 17, 1887 - June 10, 1940)." National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/individuals/marcus-garvey

-

"Marcus Garvey: Biography, Black Nationalism Activist, Businessman." Biography.com, updated 2025. https://www.biography.com/activists/marcus-garvey

-

"Marcus Garvey Park Highlights." NYC Parks. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/marcus-garvey-park/history

-

"Marcus Garvey: Quotes, Books & Death." HISTORY. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/marcus-garvey

-

"Marcus Garvey Timeline." PBS American Experience. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/garvey-timeline/

-

"More Than a Century After His Conviction, Marcus Garvey Receives Pardon for Mail Fraud." Biography.com, 2025. https://www.biography.com/activists/marcus-garvey

-

"Remembering Marcus Garvey." Jamaica Information Service. https://jis.gov.jm/information/get-the-facts/remembering-marcus-garvey/

-

"The Black Star Line." Steamship Historical Society, 2020. https://shiphistory.org/2020/01/20/the-black-star-line/

-

"Tracing the Life of Marcus Garvey in New York City." Untapped New York, 2020. https://untappedcities.com/2020/12/04/tracing-marcus-garvey-nyc/

-

"Universal Negro Improvement Association." PBS American Experience. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/garvey-unia/

-

Ramla Marie Bandele. "'Black Moses' Lives On: How Marcus Garvey's Vision Still Resonates." NPR Throughline, February 8, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/08/965503687/marcus-garvey-pan-africanist